The ARRIVE trial – should it influence practice in New Zealand?

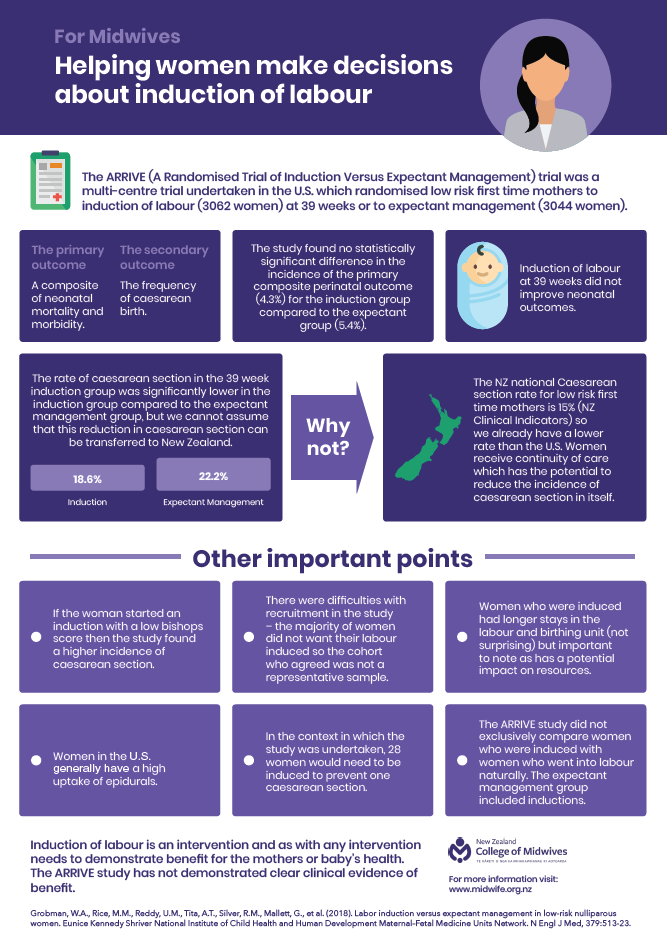

The ARRIVE Trial is a recently published large United States multicentre randomised control trial (RCT) which was undertaken to test the hypothesis that induction of labour at 39 weeks resulted in better outcomes for low risk nulliparous women 1. The primary outcome for the study was a composite of perinatal death or severe neonatal complications and the principal secondary outcome was caesarean section.

The intervention arm was randomised to induction of labour between 39+0 to 39+4 weeks, while women in the control arm were randomised to ‘forgo elective delivery before 40 week +5 day’s and were to have ‘instigated delivery’ by 42+2 weeks.

The risk of the primary composite perinatal outcome (perinatal death or severe neonatal complications) was 4.3% for the induction group compared to 5.4% in the control group. Although clearly different, the results did not reach statistical significance and thus are reported as ‘no difference’. Of importance, however, was the reduced rate of caesarean section in the 39 week induction group which was 18.6% compared to 22.2% in the control group (expectant management), which was a statistically significant difference.

The study’s authors conclude that Induction of labour at 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparous women resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of caesarean section.

Why is this trial important?

The trial has already generated a large volume of discussion internationally and has the potential to influence obstetric practice globally. The reasons for this are:

- It is a randomised controlled trial – therefore considered high level evidence

- It addresses existing concerns about the ‘too high’ caesarean section rate and provides a potential way of reducing it

- It fits a philosophy that considers the woman’s body to be ‘faulty’, raises anxiety and undermines trust in the woman’s own physiology

The findings of the ARRIVE trial dispute the many previously published observational studies that have demonstrated induction of labour increases the risk of caesarean section when compared to spontaneous labour 2-6.

Whilst it is only one study, it includes a large cohort of women and because of the methodology (RCT) the results are deemed more reliable than in other types of studies. However, as with all research methodologies, there are still a variety of issues within the study and a number of reasons why this study needs careful consideration.

Randomised controlled trials are thought to be the most scientific method for testing treatment options and are optimum when the treatment or intervention is simple – one drug versus placebo or one procedure versus a placebo. Induction of labour is a complex procedure which uses not just a variety of different drugs (and strengths of drugs) but also different care provision during labour. Subjective judgements are made (different Bishops scores may result in different treatments) and subjective decision making occurs (decision when/whether there is a need for caesarean section), none of which can be fully covered by a protocol but do undermine the ability to ensure consistency within the study and can influence the outcomes.

When faced with new evidence it is useful to ask some questions of that evidence. Namely, would the intervention or practice change be acceptable within our context, is the setting/population/protocols in our context the same as that of the study environment and if so would the results be the same? Whilst the results may be statistically significant there is a need to also consider whether they are clinically significant particularly in a different context to the trial setting. We need to examine the evidence carefully, review these questions and determine what the potential benefits and harms of adapting the change into practice would be for our context?

1 – Would Induction of labour at 39 weeks be acceptable to women?

Induction of labour is an intervention, which requires a vaginal examination to determine the readiness of the cervix for labour, then potential cervical ripening methods, to help improve induction outcomes. Finally, it requires that hormones are administered vaginally and/or intravenously to stimulate labour. This leads to an increased need for analgesia (most commonly epidural anaesthesia), and fetal monitoring so women are unable to move freely during labour. Induction of labour results in a longer labour and specifically a longer latent phase of labour 7.

The intervention was not acceptable to many women eligible to participate within the study

Out of 22, 533 women who were eligible according to the nulliparous, singleton, low-risk pregnancy criteria, 6,106 (27%) women agreed to be randomised and 6,096 mother-baby pairs were included in the analysis.

This low rate of acceptance among women willing to be randomised to early induction of labour – (only slightly more than one in four agreed to participate) means that the sample has some inherent bias. The women who consented to participate were those who were open to having an early induction and a medicalised, hospital birth.

This is a well-documented issue with randomised trials related to pregnancy and childbirth – women want choice – and randomisation is neither acceptable to many, nor do practices undertaken under trial conditions represent real-world practice and outcomes.

This study did not test induction versus physiological birth, it tested induced medicalised, hospital birth at 39 weeks versus medicalised, hospital birth at 40+5 weeks or later, often by induction of labour.

2 – Did the setting/context/protocols differ to New Zealand?

It is important to note that the induction process in the trial was not dictated (hospitals continued with their own induction processes) but some aspects of the relatively new ‘optimal induction’ guideline in the USA were recommended. This included:

- Women with a modified Bishop score less than 5 were expected to have cervical ripening (method determined by clinician)

- Women should be allowed at least 12 hours in the latent phase (after any ripening, rupture of membranes and oxytocin use) before calling the induction ‘a failed induction’.

- Women should not be considered to be in established labour until 6cm dilated so a diagnosis of failure to progress should not be made before this stage.

Trial conditions rarely reflect the realities of practice and practice guidelines take time to transition into practice. In New Zealand there are 20 District Health Boards providing maternity care each with their own policies and protocols for inducing labour.

3 – New Zealand maternity settings and induction protocols vary to that of the study

A national consensus guideline on induction of labour is currently being progressed but is not yet completed meaning that practice around induction will continue to vary depending on the clinician and place of care. A major concern is that many NZ birthing suites are understaffed and over capacity. Women in the induction of labour group had a longer median duration of stay in the birthing suite (20 hours (IQR 13-28)) when compared to women in the expectant management group (14 hours (IQR 9-20)). Women who are induced are more likely to need an epidural or spinal anaesthesia for pain relief. In the USA epidural/spinal anaesthesia is almost routine care with 61% women having singleton vaginal births receiving an epidural/spinal 8. Both of these issues will have a direct impact on staffing and resources in a maternity service that has major midwifery understaffing concerns 9.If we induced women at 39 weeks, would the results be the same?

Comparisons between cohorts and countries are notoriously difficult due to different data sets, definitions and standards of care. The primary outcome of the study was that of neonatal health, the study demonstrated no statistical differences dependent on whether the woman was in the induction or expectant management group, although neonates in the induction group had a shorter duration of respiratory support and total hospital stay. Population level data demonstrates a lower incidence of neonatal respiratory support in New Zealand compared with that in either arm of the study. Whilst not stratified to primiparous women, the New Zealand Clinical Indicator data demonstrates that 2.0% of babies more than 37 weeks required respiratory support in 2016 10, this compares to an overall rate of 3.2% in the ARRIVE study (3% for the induction group and 4.2% in the expectant management group). So inducing women at 39 weeks is unlikely to improve this neonatal outcome in New Zealand.

For the secondary outcome, that of a reduced caesarean section rate, again population data demonstrates a lower caesarean section rate in New Zealand than that of the study. The standard primiparous women in the Maternity Clinical Indicators, is a similar group of low risk women to the study and identifies an average caesarean section rate of 15% 10. This is lower than both arms of the ARRIVE trial with 18% in the induction group and 22% in the expectant management group.

Inducing women at 39 weeks in New Zealand is unlikely to reduce the already low caesarean section rate for low risk primiparous women.

4 – What are the potential benefits and harms of adapting the change into practice for our context?

It would appear that there are few potential benefits of adapting a change in practice to inducing nulliparous women at 39 weeks gestation in New Zealand because the main benefit (lowering of caesarean section rate) is unlikely to occur.

The harms are more numerous, in that advising induction sets a woman onto a cascade of intervention that has the potential to negatively affect her experience of labour and birth. Women will have a longer labour, spend more time in the birthing suite, and be more likely to require epidural pain management. A woman’s first birth experience has profound implications for the transition of the woman to her maternal role and has the potential to have emotional and psycho-social health implications for her, the baby and the whole family. The longer term impact of the use of synthetic oxytocin itself remains unknown, with concerns raised as to whether use may alter or affect epigenetic and immunological development for the infant. These implications are not addressed by short-term ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ outcome measures in randomised trials.

There are other ways to reduce caesarean section rates

The American College of Nurse Midwives makes the crucial point that if the aim is reducing the rate of caesarean section, there are far more effective means of doing this than elective induction of labour at 39 weeks. These include:

- Continuity of care for low risk women from a known midwife 11-13

- Planning to give birth at home or in a primary unit 14-16

- Continuous labour support 13

- Moving and being in upright positions during labour and birth 17

These points are already embedded in the New Zealand maternity system which is underpinned by the Midwifery Partnership model of care, and may explain the lower caesarean section rate among low-risk nulliparous women in this country in comparison to what was able to be achieved in either arm of the ARRIVE Trial.

Conclusion

The study has provided evidence that inducing labour at 39 weeks may reduce the caesarean section rate for women in the USA who are already planning to have a medicalised labour and birth. The USA has obstetric led care, high caesarean section rates 18 and increasing maternal mortality rates 19. The results are not transferrable or generalizable to New Zealand, which has midwifery led maternity care, a lower caesarean section rate 20, and a reducing maternal mortality rate 21. Implementing a practice change to induction at 39 weeks is unlikely to provide benefit for women and their babies in New Zealand and may even cause harm. With the possibility of an increase in the caesarean section rate to USA levels due to the undermining of care that supports physiological labour and birth. It is important that we continue to share information about induction of labour with women and maintain policies of waiting until 41 weeks to discuss and refer for induction of labour by 42 weeks.

References

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor Induction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women. N Engl J Med 2018;379:513-23.

- Dunne C, Da Silva O, Schmidt G, Natale R. Outcomes of elective labour induction and elective caesaran section inlow-risk pregnancies between 37 and 41 weeks gestation. Journal Obstetricians & Gyncaecologists Canada 2009;31:1124-30.

- Ehrenthal DB, Jiang X, Strobino DM. Labor induction and the risk of a cesarean delivery among nulliparous women at term. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:35-42.

- Glantz JC. Term labor induction compared with expectant management. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:70-6.

- Guerra G, Cecati J, Souza J, al. E. Elective induction versus spontanous labour in Latin America. Bulletin World Health Organisation 2011;89:657-65.

- Vardo J, Thornburg L, Glantz J. Maternal and neonatal morbidity among nulliparous women undergoing elective induction of labour. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2011;56:25-30.

- Harper LM, Caughey AB, Odibo AO, Roehl KA, Zhao Q, Cahill AG. Normal progress of induced labor. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:1113-8.

- Osterman M, Martin J. Epidural and Spinal Anesthesia Use During Labor: 27 state Reporting Area, 2008. National vital Statistics Reports 2011;59.

- (TAS) TAS. Workforce Information Report: The New Zealand District Health Boards’ Midwifery Workforce. Wellington: Central Regionsl Technical Advisory Services Ltd; 2018.

- Ministry of Health. New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators 2016. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2018.

- Tracy SK, Hartz DL, Tracy MB, et al. Caseload midwifery care versus standard maternity care for women of any risk: M@NGO, a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2013;382:1723-32.

- Rayment-Jones H, Murrells T, Sandall J. An investigation of the relationship between the caseload model of midwifery for socially disadvantaged women and childbirth outcomes using routine data – A retrospective, observational study. Midwifery 2015;31:409-17.

- Bohren M, Hofmeyr G, Skala C, Fukuzawa R, Cuthbert A. Continuous support for women durng childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Art. No.: CD0037662017.

- Bailey DJ. Birth outcomes for women using free-standing birth centers in South Auckland, New Zealand. Birth 2017;44:246-51.

- Birthplace in England Collaborative Group. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. BMJ2011.

- Davis D, Baddock S, Pairman S, et al. Planned Place of Birth in New Zealand: Does it Affect Mode of Birth and Intervention Rates Among Low-Risk Women? Birth 2011;38:111-9.

- Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, Styles C. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013.

- Martin J, Hamiton B, Osterman M, Driscoll A, Mattews T, Division of Vital Statistics. Birts: final Data fo 2015. National vital Statistics Reports 2017;66.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate: Disentangling Trends From Measurement Issues. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:447-55.

- Ministry of Health. Report on maternity 2015. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2017.

- Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee. Twelfth Annual Report of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee: REporting mortality and morbidity 2016. Wellington: Heath Quality & Safety Commission; 2018.